(2020年6月)萧梅 | 《七十二家房客》的记忆:上海日常生活中的声音景观

*2014年8月21日至24日,欧洲中国音乐研究基金“磬(CHIME)”第18届国际研讨会在丹麦奥胡斯大学召开。会议主题为“Sound,Noise And The Everyday:Soundscapes in China”(声音、噪音和日常生活:当代中国的音景)。此篇为萧梅教授应邀在是次会议上做主旨报告(keynote)的发言稿。

作者简介:萧梅,上海音乐学院音乐学系教授。

As a keynote speaker in English, for me, thisisfirst time. I felt a little bit nervous when I was askedby Frank. But Frank said:Pleasedon't worry at all about the task of giving a keynote speech. There are no specialdemands. In CHIME conferences, we don't expect keynote speakers to be more 'clever', more deep or more entertaining than anyone else. We all belong to the same family of scholars. Of course it's a good thing to be entertaining,andinformative, and a little provocative. But that is true for all of us. He suggested that I could simply talk about the topic that I originally planned to talk about, our project ofeveryday'sounds' from different parts of China.

(树叶风声:0′00″—0′26″;破宫产及新生儿啼哭声:0′26″—0′56″;黑知了鸣叫:0′56″—1′06″;绿知了鸣叫:1′06″—1′16″;蟋蟀鸣叫:1′17″—1′33″)

First of all, I would like to play two recordings for you:

1.The sound is so ordinary that we don’t notice it in our daily lives. In this field recording, our students differentiated sound-marks, keynote and sound signals and became aware that paying full attention to the “acoustic perfume”, which is common in an academic institution, will probably make us neglect the natural sounds around us. That is to say, music, as an artificial and invented soundscape, working like a sound wall, overshadows the “Lo-fi” soundscape made up of such naturalsoundas falling leaves, wind, footsteps, etc.

2.Among these sounds, the doctors and the mother only noticed the crying and completely ignored the other sounds, because the doctors usually judge the health condition of the baby according to its crying, and for the mother, the crying carries so much emotional significance. However, the students, who were first exposed to such sounds, were fully drawn by those strange sounds, which turned out to be the suction apparatus.

Thus the students realizedthatexperience of sound is not only objective but also subjective.

Our project is named ‘Sounding China---- audio-visual ethnography on eco-musicology’. It included 9 sub-groups, such as the Multi-part sounds in the steppe of North China, which also participates in this conference. Among these sub-groups, Shanghai City Soundscapes is the only purely audio project.

It is noteworthy that in China, soundscape or acoustic ecology has made much greater achievement in urban architecture and design than in musicology. To promote this kind of research, we havedonea series of special articles, international courses, and workshops.

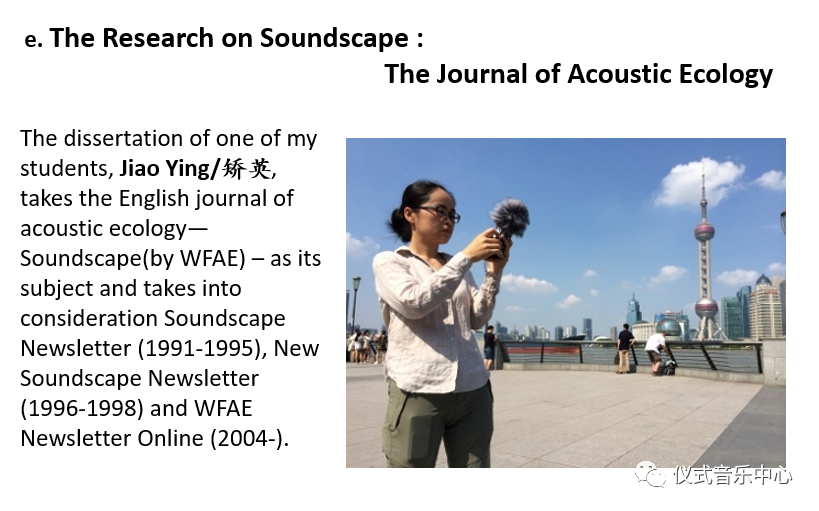

Mystudents,Jiao Ying,takesthe English journal of acoustic ecology—Soundscape as a research project for her dissertation. This can be said to be an unprecedented research in the world.

About Shanghai urban soundscape,I’d like to mention, Yan Jun, an “sound artist”, he published his famous Qiujiang Road in 2008. He recycled the sounds from a road in the marginal area of Shanghai, which abounds with shops selling cheap digital products, machine parts and second-hand machines. Interestingly, it was from my daughter, who studied at our conservatory that I got to know and began to pay attention to such a group of people who also work on field recording, but with purposes different from collecting and compiling traditional music, that is, different from ours. With such sound artwork as Qiujiang Road, Yan Jun isdoubtlesslya pioneer in collecting “Shanghai Soundscapes”.

Another person I’ll introduce who isanPhilippinesAmerican, Terence Lloren(罗天瑞)。Hetakedup a project “growing up with shanghai” from 2009, and made a work which was called“Shanghai in the Voice”.

When we did ourprojects,wearemost concerned with one problem: what soundscape is special enough to differentiate Shanghai from other cities? In other words, how can we “hear” Shanghai,exceptits dialect?

(上海外滩钟声:0′00″—1′55″;香港钟声:1′56″—2′22″)

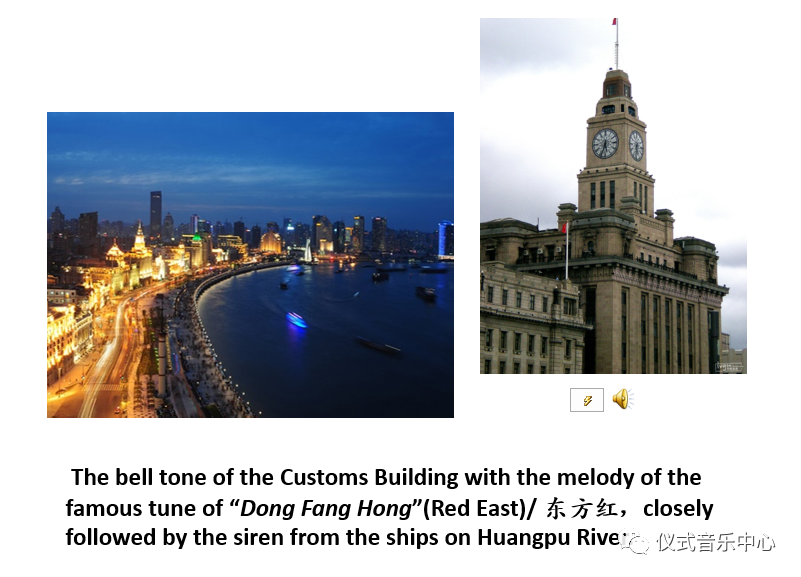

Onedayafternoon, when we were searching for material in Shanghai Municipal Archives on the Bund, my students and I suddenly heard the bell tone of the Customs Building nearby, with the melody of the famous tune of “Dong Fang Hong”, closely followed by the siren from the ships on Huangpu River. These two kinds of sound, intertwined with each other, just like a sound-mark, instantaneously inspired our sense of the acoustic “localness”. We can hear the bell’s sound in many places in the world, but not necessarily accompanied by the siren of ships; even if thereissiren, it is impossible to find another bell playing “Dong Fang Hong”.

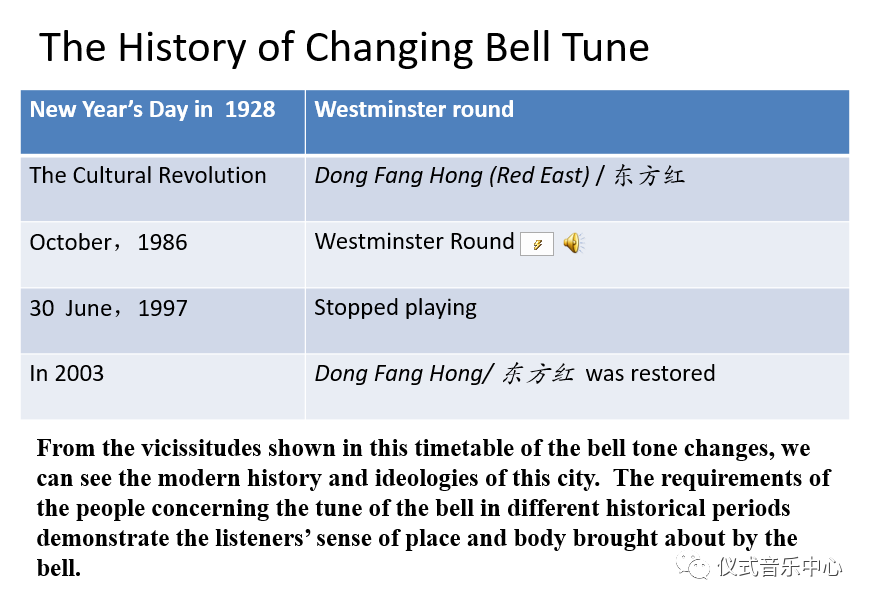

But the question is, nearly 40 years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, why does the bell still play this song? Then we investigated the history of the belltone. On New Year’s Day in 1928, this “biggest bell in Asia”, made its first sound,playing“Westminster round”. When the Cultural Revolution began, the tune was replaced by that of “Dong Fang Hong”.

Andthanit has changed again and again ,you can see the timetable.

This bell can be regarded as thesonoriclandscape on the Bund of Shanghai. In this investigation, however, I found that the Shanghainese above 50 years old have a clear memory of “Dong Fang Hong” replacing “Westminster round”, but don’t remember much about the changes after that. This means the decrease of the importance of the bell tone to the daily life of the citizens and the weakening of their historical sense of the city, probably caused by the changes in the ways of their lives. For example, as I remember, the Bund always served as a huge public park for the Shanghai people, and the bell tone on the Bund also functioned as the standard time for many citizens. Now, the Bund has become aturistattraction instead of playing a role in the local people’s life.

The fact that the bell tone rouses different feelings demonstrates that sound is not simply an object to be measured scientifically, but an event to be experienced.

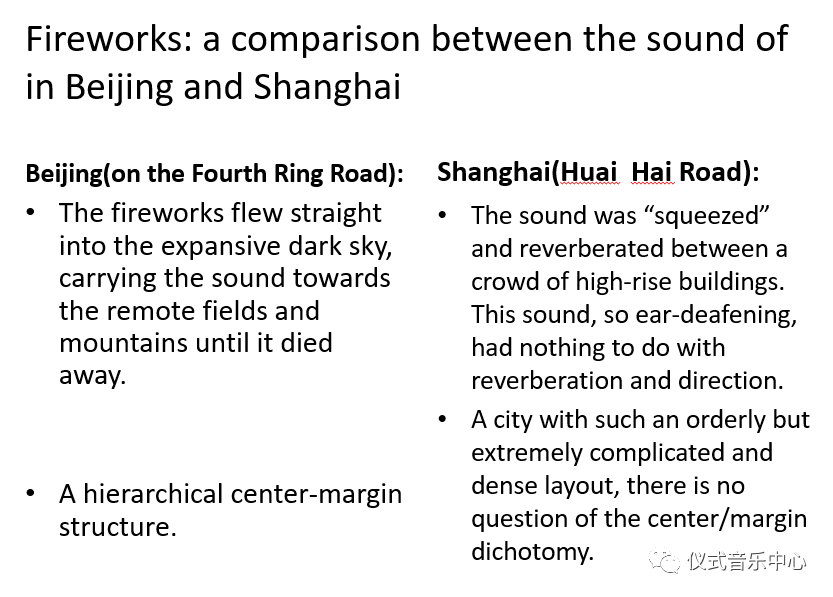

Another factor that helped to form my experience of Shanghai’s soundscapeisa comparison between the sound of fireworks in Beijing and Shanghai. On the moment when the Chinese New Years’ Day came in 2010, I listened to the fireworks on the fourth ring road of Beijing. The fireworks flew straight into the expansive dark sky, carrying the sound towards the remote fields and mountains until it died away. At the same moment of the next year, I was doing the same thing on West Huaihai Road in Shanghai. The sound, though generated by the same kind of thing, was “squeezed” and reverberated between a crowd of high-rise buildings. This sound, so ear-deafening, had nothing to do with reverberation and direction, onlymovingin a fluctuating stasis.

The two kinds of firework sound communicate two different senses of place. The firework sound in Beijing reminds me of the city’s strict layout as well as its traditional administrative management. Specifically, as the capital city with a long history, Beijing has a hierarchical center-margin structure, whose influence can still be seenfromtoday’s organization of residential communities and the names of the streets. The situation in Shanghai is quite different. In a city with such an orderly but extremely complicated and dense layout, there is no questionofthe center/margin dichotomy. All the fireworks fuse with each other in the narrow space of the city, creating a resounding and complex sonic field, in which it is impossible to trace any single sound. Crowded, flourishing, full of possibilities and uncertainty, that is exactly what the Chinese people think of Shanghai.

After a long preface, now I’ll talk about my topic and focus on how the sense of place of sound by different livingspace.

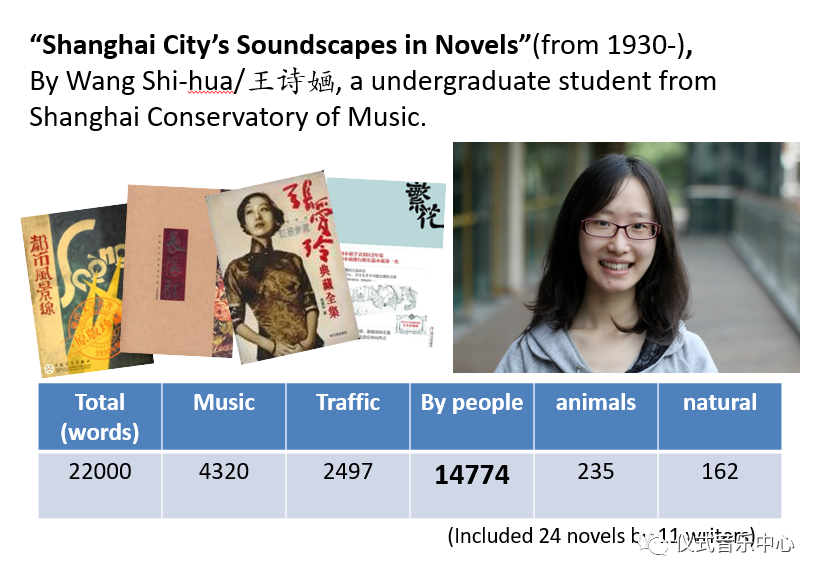

She is our groupmembers,Wang Shihua, a seniorundergraduatesin musicology at Shanghaiconservatoryof Music. She did a research on the description of Shanghai’s soundscape found in the modern realist novels with Shanghai as background and by writers living in this city. The works she chose cover a span from the 1930s to the present, including 24 novels by 11 writers. From these novels, she extracted excerpts depicting sounds, and classified these excerpts and made a statistical study of them. You can see the result is, most of the wordsofsounds made by people from living space.

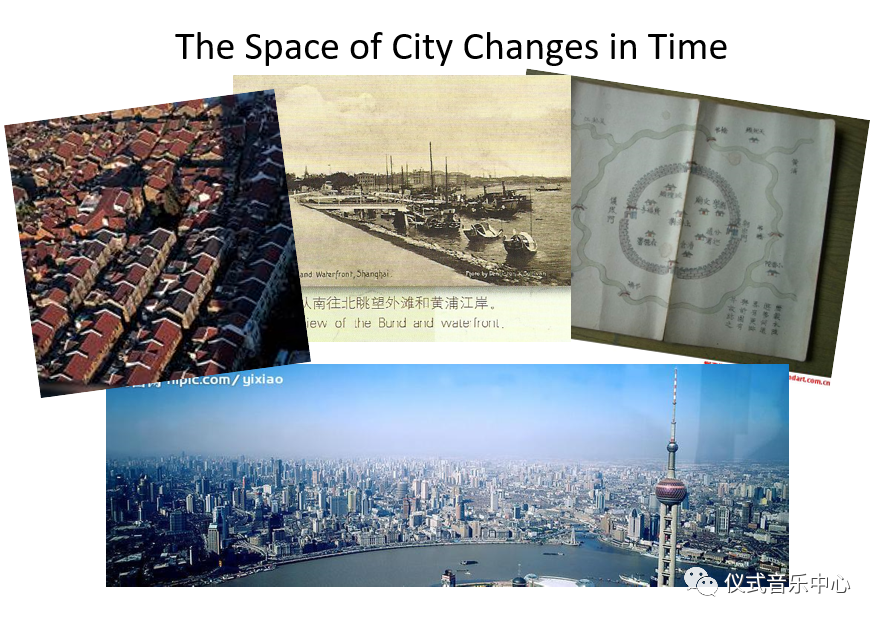

The soundscapes are closely relatedwitharchitectures.

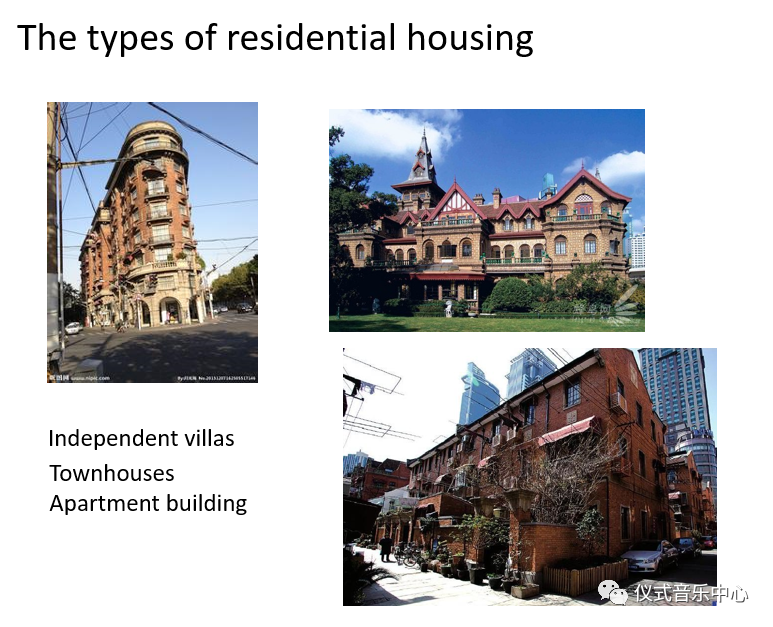

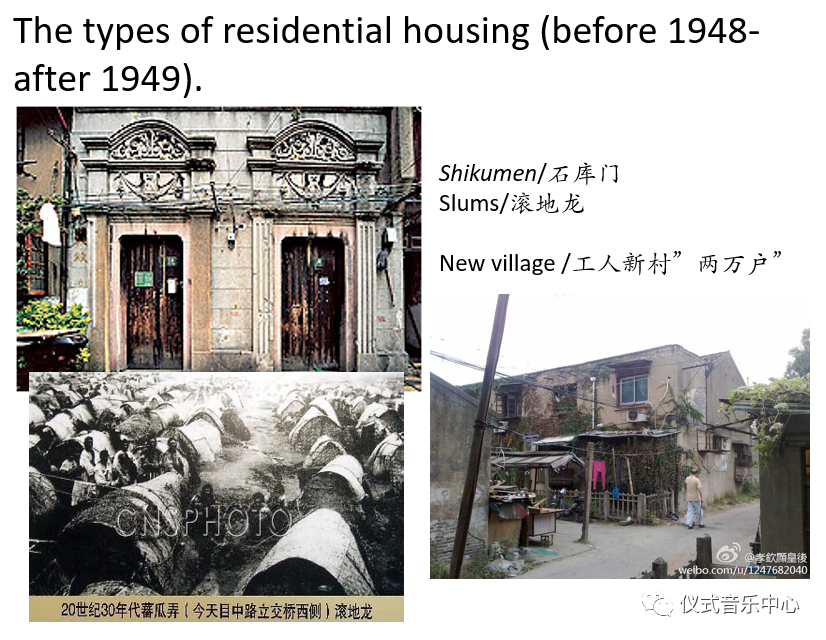

Take the types of residential housingasexample. There were independent villas, townhouses, apartment buildings,Shikumen, shanty towns and slums. After 1949, a new residential community appeared in which two-storey apartment buildings were built for those who used to live in shanty towns and slums and for the newly employed workers. Each building has ten rooms with sharedatoilet andakitchen. Such a community, called a “new village for workers”, could accommodate about twenty thousand households(两万户). All these various residential types represent different living environments and social statuses of the residents.

Among these buildings as symbols of social ranks, the sense of place of sound is also divided. For instance, lives in villas often strike us as mysterious, for people outside the private garden or yard cannot see through. As to the townhouses, also known as “new style longtang”, “a big family usually takes up two such houses, separated by a garden or Longtang, so rings are needed to call everyone to dinner.” (quoted from Cheng Naishan’sA Sketch of Shanghai).

According to the space and perceptual experience of sound we mentioned above, it is clear that what we hear and how we listen not only direct our attention, but also shape our social consciousness, our social relationships and our daily lives.

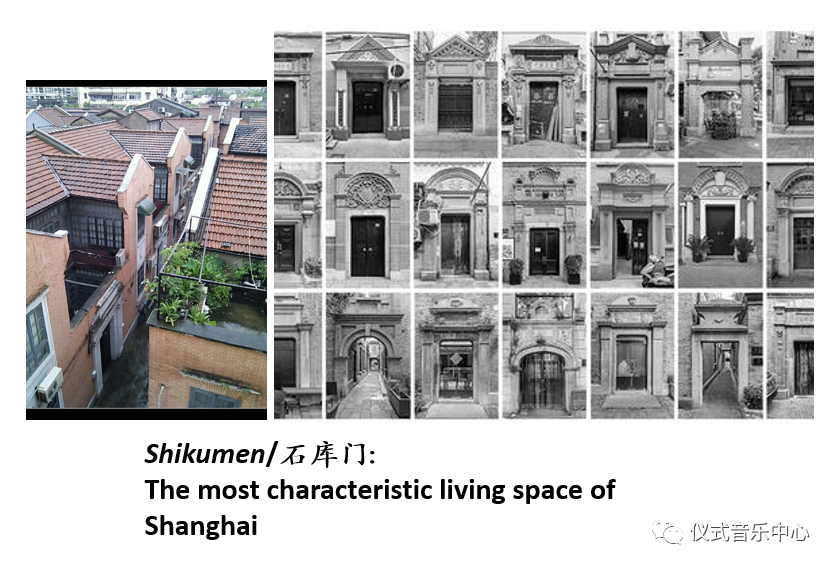

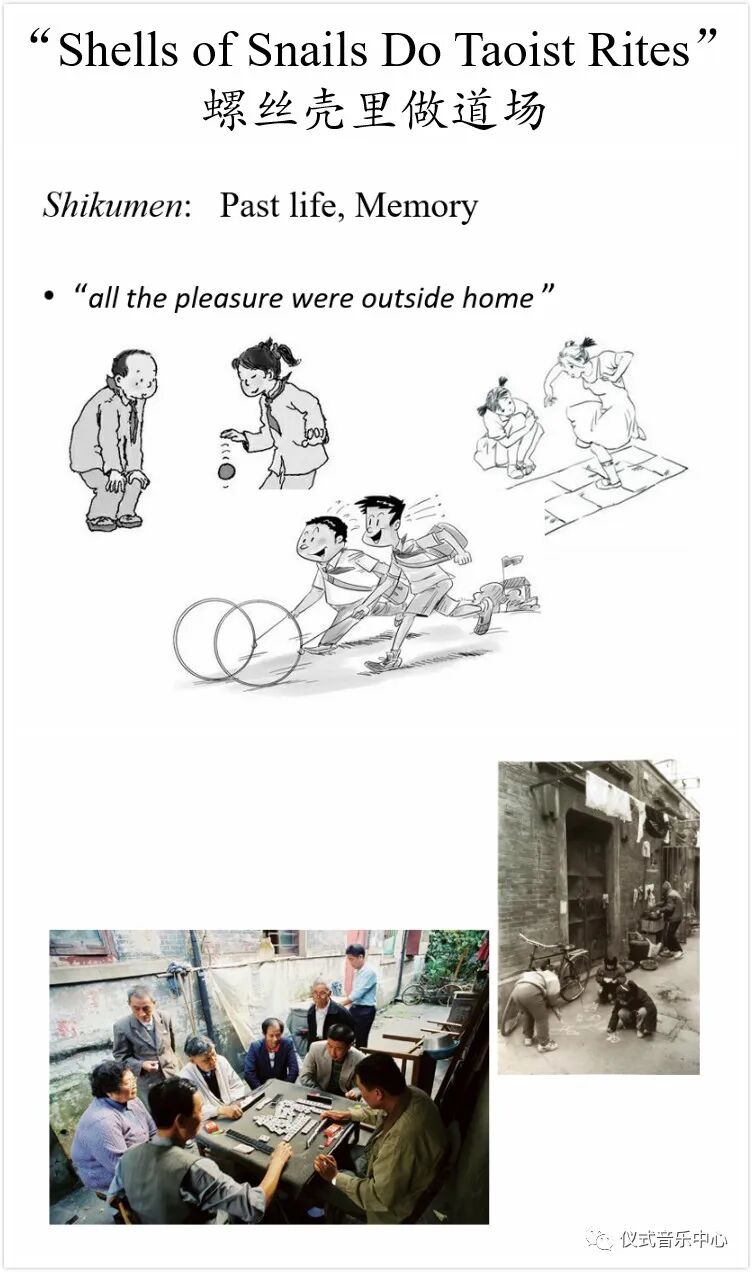

Although our project deals with many aspects of Shanghai’s soundscape, but I want tofocuseon Shikumen, the most characteristic living space of Shanghai and discuss the sounds and sonic experience in this particular environment and its personal relationships.

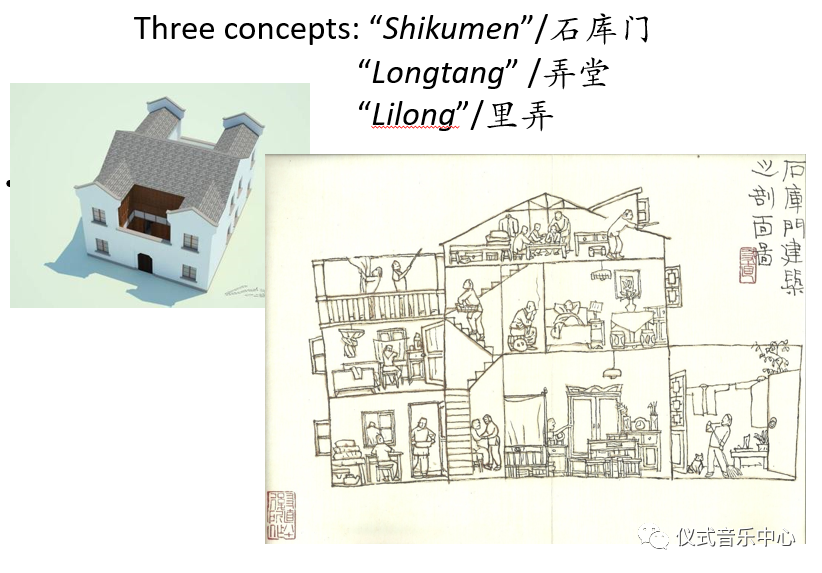

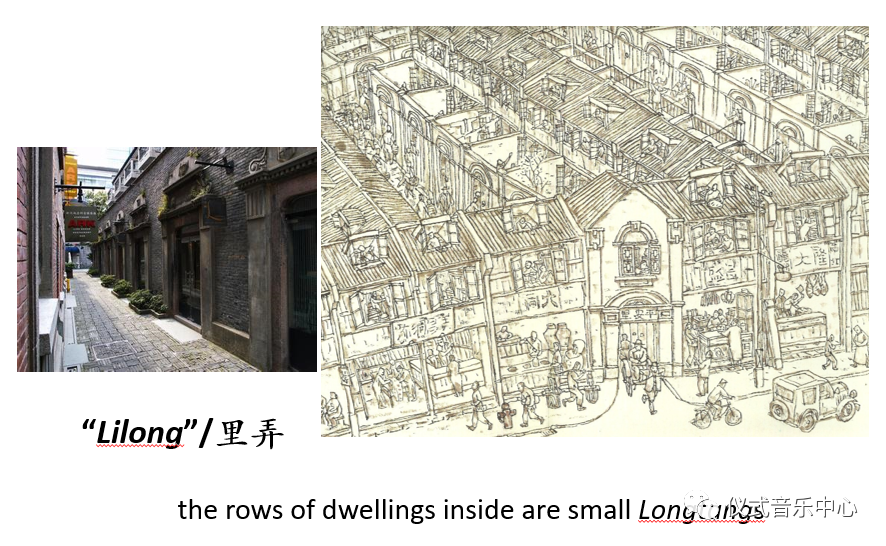

There are three concepts: “Shikumen”, “Longtang” and “Lilong”.

Shikumen literally means “stone warehouse gate”, because the maingatesaremade of stone.

As this planofShikumen shows, we can see the front door, the front courtyard, the hall, the wings, the pergola room, the attic…. It obviously combines Western and Chinese architectural elements. It preserves the traditional Chinese lifestyle of extended families on the one hand, and is adapted to the newer lifestyles of more and more nuclear families and single residents.

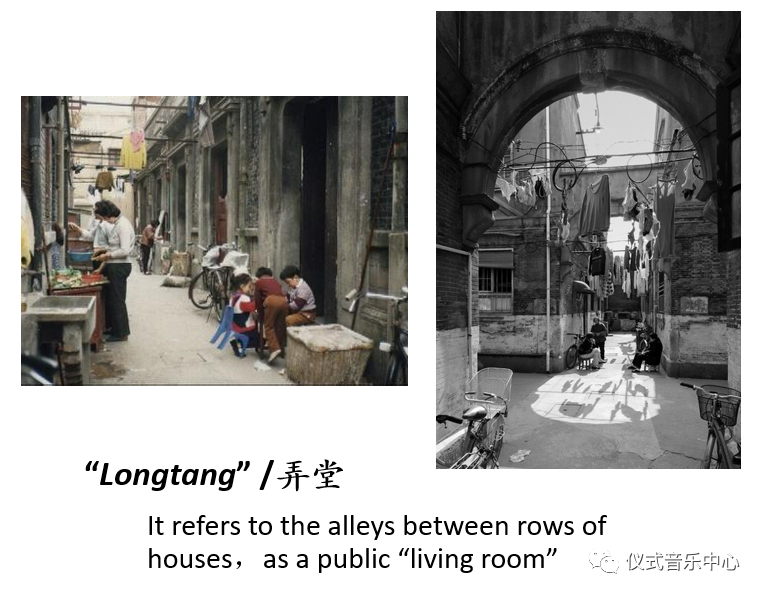

And whatis Longtang? It refers to the alleys between rows of houses. Each house has a front door and a back door, and the back doors of one row of houses are just face to face with the front doors of another row. And the area in between is actually a public “living room”.

As to “Lilong”, please look at the picture: this is the alley, surrounding an area of dwellings; here is the gate at the entrance into this area, and the name of the area iscoveredon the gate. Going through this gate we are in what is called the big longtang, and the rows of dwellings inside are small longtangs, also known as lilong, meaning the inside longtang.

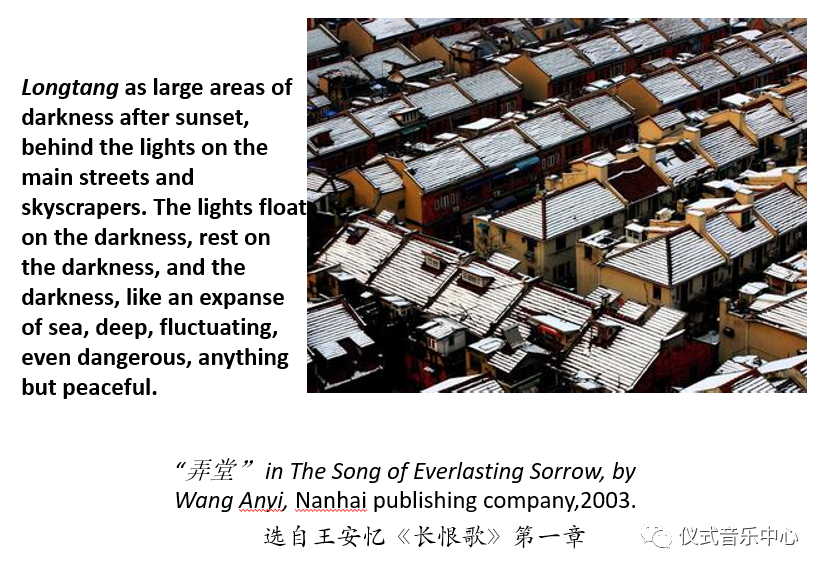

In her famous novel, Wang Anyi, one of the most accomplished Chinese contemporary writers, dedicated the whole first chapter to “longtang”, which she regarded as the distinctive background against which this story of Shanghai unfolded. She described longtang as large areas of darkness after sunset, behind the lights on the main streets and skyscrapers. This description tells us the fact that it is not the glorious and luxurious appearances but the life in the “dark” longtangs that constitutes the basis and main body of the urban life of Shanghai.

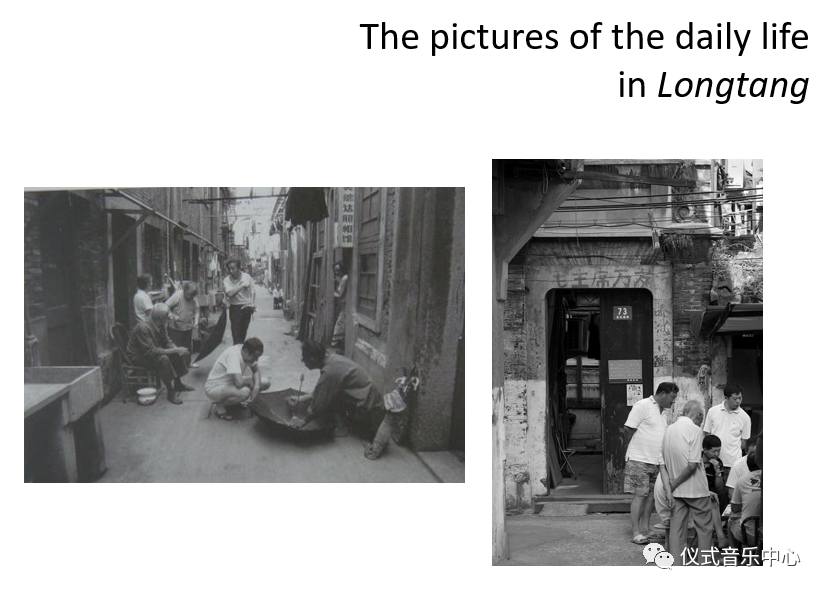

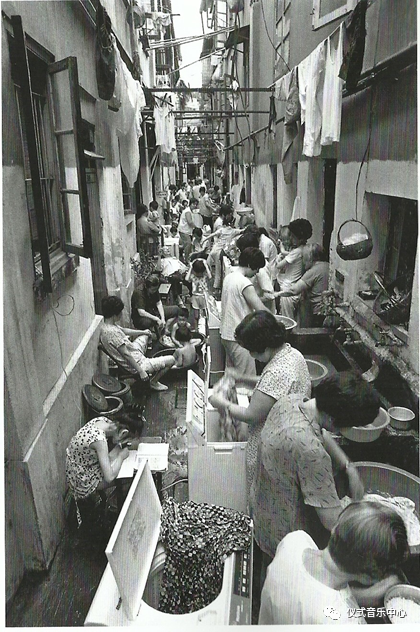

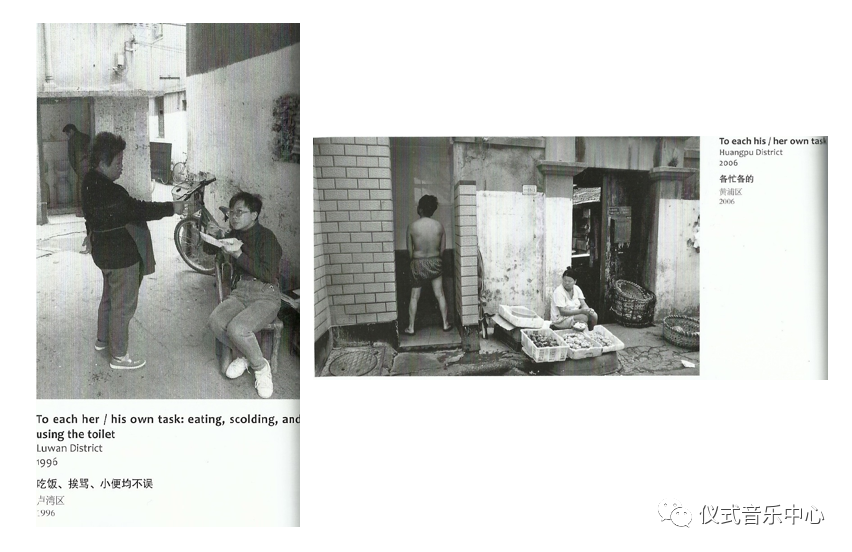

Here are some pictures of the daily life inlongtang. It must be unthinkable for the Scandinavians to live in such a crowded and narrow place.

We can seethatpeople living here have almost no privacy. Is there any sound inadaily life in such space? What kinds ofsoundare made? How do such sounds interact with the human behavior, emotions and relationships?

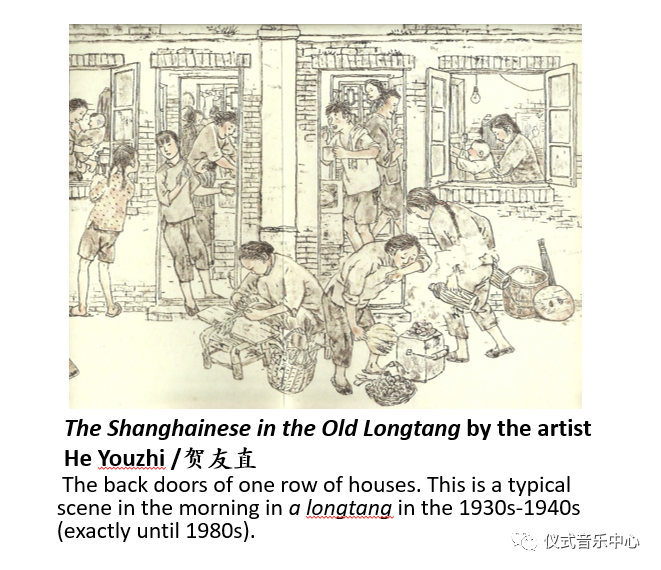

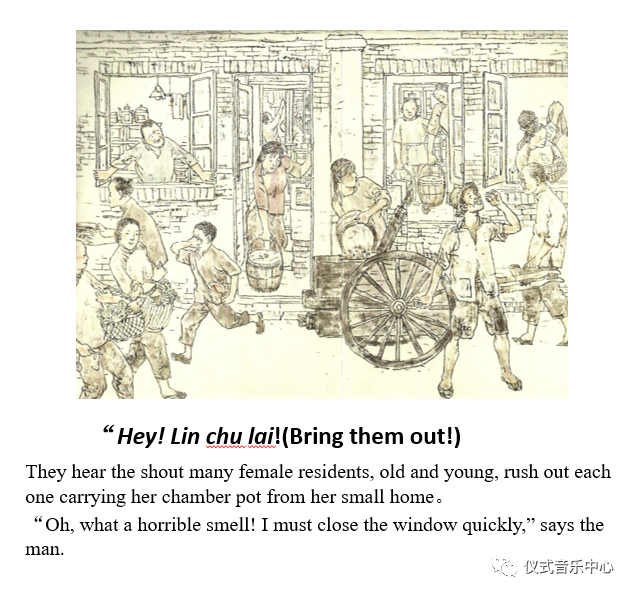

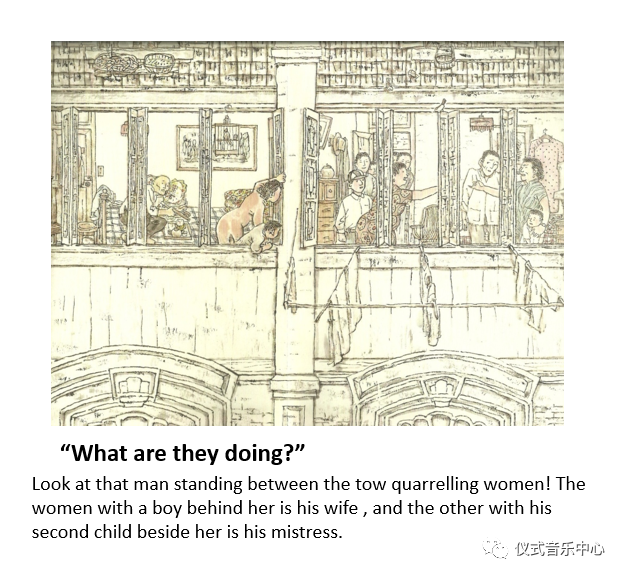

“The house with 72 tenants” has become a fixed expression of the lives inlongtang. Among paintings and pictures that depictlongtang,TheShanghainese in the Old Longtang by the artist He Youzhi can best present the soundscape in this particular environment.

1.The backdoorsofonerow of houses. This is a typical scene in the morning in a longtang in the 1930s-1940s (exactly until 1980s).A woman lighting a coal ball stove outside the back of the house and the others brushing teeth and washing face, clothes and so on.

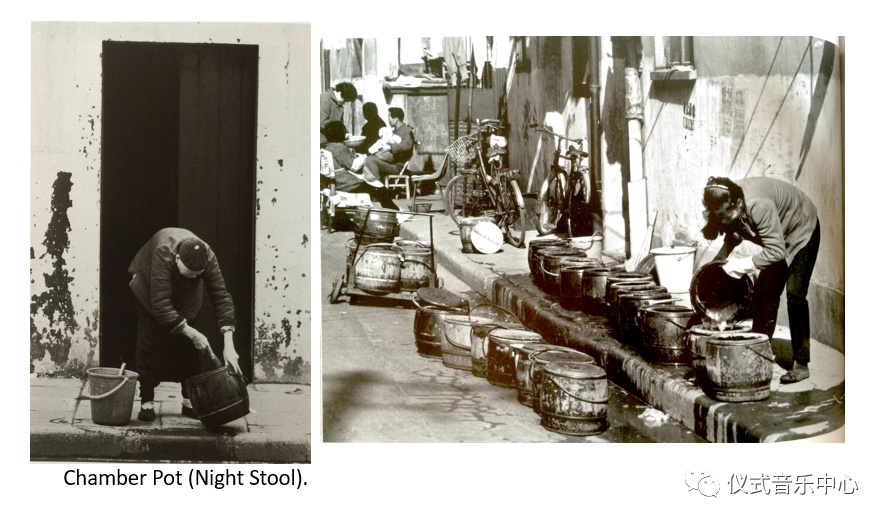

2.Hey! Lin chu lai! His loud voice plus the sound of the cleaning of the Night stools

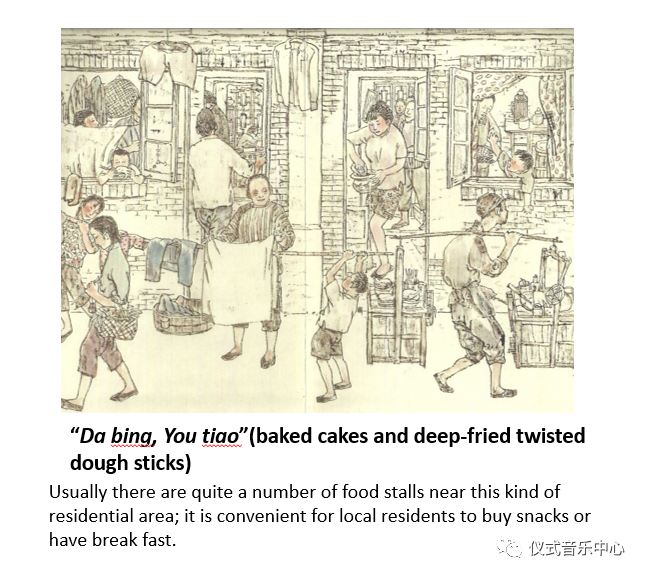

3.“Da bing you tiao!” You can see the pictureonbuying food or selling breakfast, the hawkers’ shouting and sometimes the babies crying to be fed make the longtang very lively. There is a special ‘concert’ here every morning.

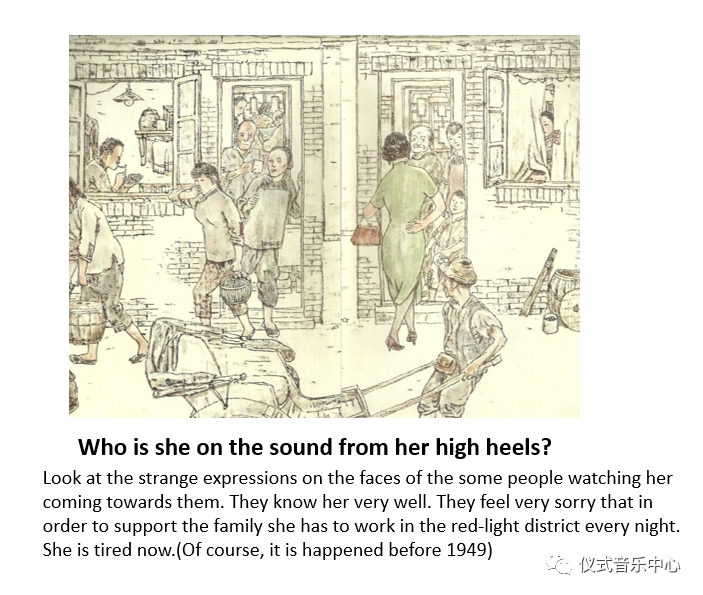

4.Look at the strange expressions on the faces of the other people watching her coming towards them. They know her very well. They feel very sorry that in order to support the family she has to work in the red-light district every night. She is tired now. (do youhearedher heel’s sound?)

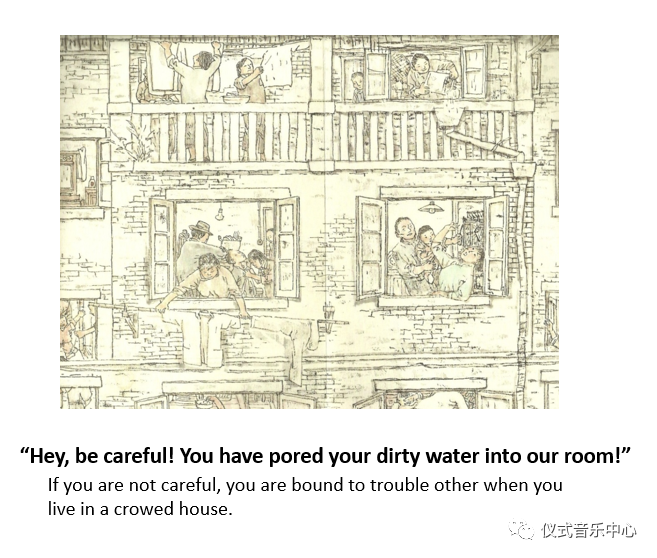

5.Hey, be careful. Someone lived upstairs (tiny roof),haveto pour water slowly, in case of splashing into the downstairs home.

6.“What are they doing?” Both the mother and her son are curious about what is going on in the house next door. That peer around the window trying to see, very inquisitive.

[Living in this kind of house, one cannot worry too much about privacy.]

For my experience, I still remember hearing the sound of snoring and peeing from the neighbors during the night when I was a teenager. There was one family with fivekidsin the upstairs of my grandfather’s home. In the early 1980s, when I visited there, three boys of the five had got married and still lived in the same place, only separated by thin clapboards and curtains. Everything could be heard; everyone was listening. Such a living space inevitably had an influence on people’s behavior and state of mind.

Now we might as well quote several passages from literary works by Shanghai writers.

1.A passage quoted from Ba Jin’sDestruction.

This passage describes various sounds in a household as well as the people who made them. The writer also used the effect of synaesthesia, comparing the eras to the eyes.

2.A passage quoted from Jin Yucheng’sBloomingFlowers.

This passage tells us that there was only a singlelayerfloor between upstairs and downstairs, and the floor had cracks. One can hear what the neighbors are doing.

3.A passage quoted from Wang Anyi’sPassingBy.

The back door opened, making a squeaky noise anditclosed gently. Then there were footsteps on thestair.

4.The voice of the mother-in-law came from the next room, very loud.

All of the four passages above convey the experience of overhearing and eavesdropping.

5.In the next passage from Jin Chengyu’sBlooming Flowers,we will hear the peculiar sounds madeina very small and crude toilet:

This passage describes the embarrassing experience of a toilet user hearing the sounds of a fellow user.( 虽不见人,却比见了人还尴尬/ Is no one, but itthanthose who see the embarrassment.)

6.Here is another passagefromBloomingFlowers.

This “symphony” of sounds is an ordeal that each person living inlongtangmust undergo. This may explain the bad temper of many Shanghai women whoiscalled female tiger(母老虎). They always have to fight for the interest of their own families to survive insocrowded places.

The rise ofShikumenin the first place was a response to the increased need of migrants who moved to Shanghai. So in one single longtang, we can hear all sorts of dialects from Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Guangdong provinces. Consequently, the complex of languages is an important feature of the soundscapes here, reminding us that Shanghai is a city of migrants.

Due to such crowdedness, many old Shanghainese we interviewed, who used to live in Shikumen recalled that “all the pleasurewereoutside home”. In the early evening, people spent their leisure time outdoors chatting, telling story, playing poker or mahjong, even making fun of certain neighbors.

I’ll give you two examples of our interviews.

1. “There used to be a fat guy in the longtang, and we would make fun of him by singing ‘large body, large body …’ Wearing wooden slippers, we stamped our feetwiththe tune. A bunch of naughty boys.”

2. “I spent much of my childhood learning to play the cello, and I rarely went out to play. So I was alienated from other kids in thelongtang. My daily practice also became annoying to the neighbors. As a result, I was often bullied by other kids; they even made fun of me with the melody I played,‘LaMiMiMi Mi Re Mi Fa Sol…..’”

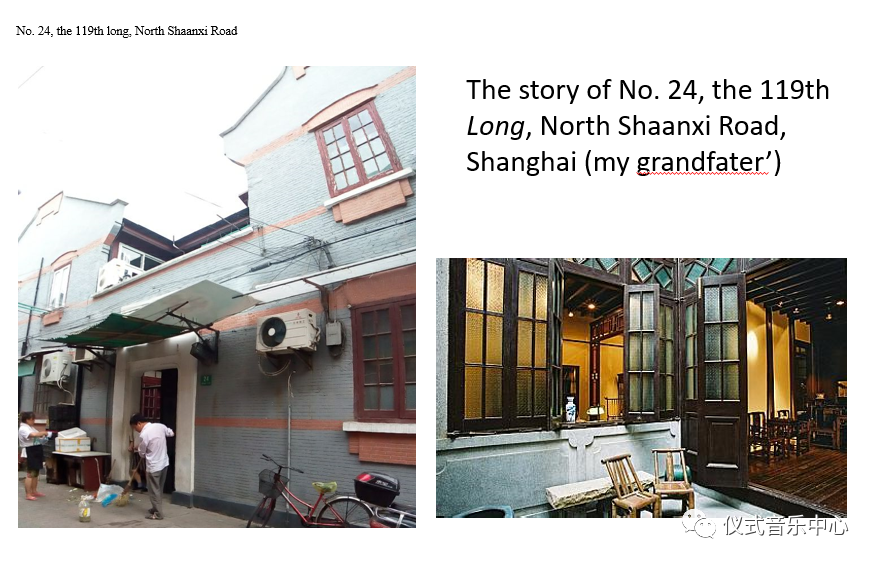

This is the front gate to the house at No. 24, the 119thlong, North Shaanxi Road. And this is the entranceintomy grandfather’s home. I came to this place for the first time at the age of five, when there were much fewer tenants, and the front courtyard and the hallwerepublic sphere. My grandmother told me that in the first half of the 20th century, this hall used to be something like a saloon for playing Guangdong music. Several artists, both professional and amateur, had been regular guests. (Actually, many meeting centers for various kinds of traditional music were set in halls of Shikumen, rather than pavilions on lakes or tea houses.) However, by the early period of the Cultural Revolution, the hall had been taken up as a dwelling. Nowadays, it has been rented to migrants as a little shop(vegetable vendor). The history of this ordinary hall tells us that the soundscape in Shikumen has been altering with the change of the life here.

When I returned to the longtang where I used to live and did my field recording this year, the more than ten gas-ovens in the kitchenhasreduced to three ovens. In our 24 hours’ continual recording, we could not find a single situation with more than three people talking. The former public “living room” has been deserted. With television and the Internet in each household, no one needs to watch the Japanese or South Koreansoupoperas using the shared TV set; with air-conditioner in every family, no one wants to enjoy the cool air outside in summer. Instead, electroacoustic has become a new part of the soundscapes.

Inthe other hand, beginning in the late 1980s, more and more high apartment buildings replaced longtangs, and the old Shanghainese moved into the modern apartments.

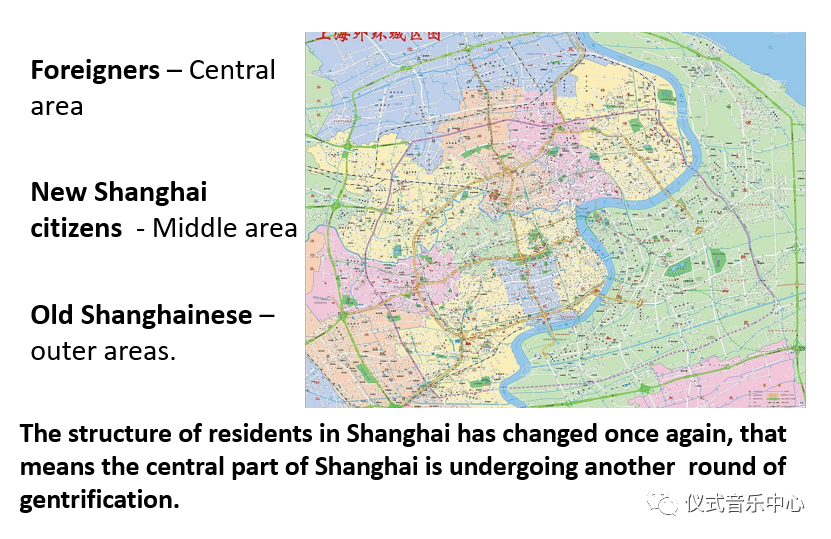

In recent years, the structure of the residents in Shanghai has changed once again. Foreigners, many of whom work in international firms, live in the central area of the city. The outer areas, which used to be countryside, have become new districts, into which the old Shanghainese moved from Shikumen. In the areas between these two parts live the new Shanghai citizens who came from other provinces andgetsettled here. Thus the central part of Shanghai is undergoing another round of gentrification.

But after many years, most of our interviewees portrayed a nostalgicsensationtowards their years spent in Shikumen. As you have seen, what I have talked about is a description of the past life, a memory. This is what impressed us the mostinthis time of fieldwork. What people miss most is the intimate relationshipbetweenneighbors. As Shen Jialuworte,“in the longtangs of Shikumen 30 years ago, people were close to each other without much vigilance.”They helped each other, shared with each other, communicated with each other. All these came to an end with the establishment of the new lifestyle in apartmentbuilding.

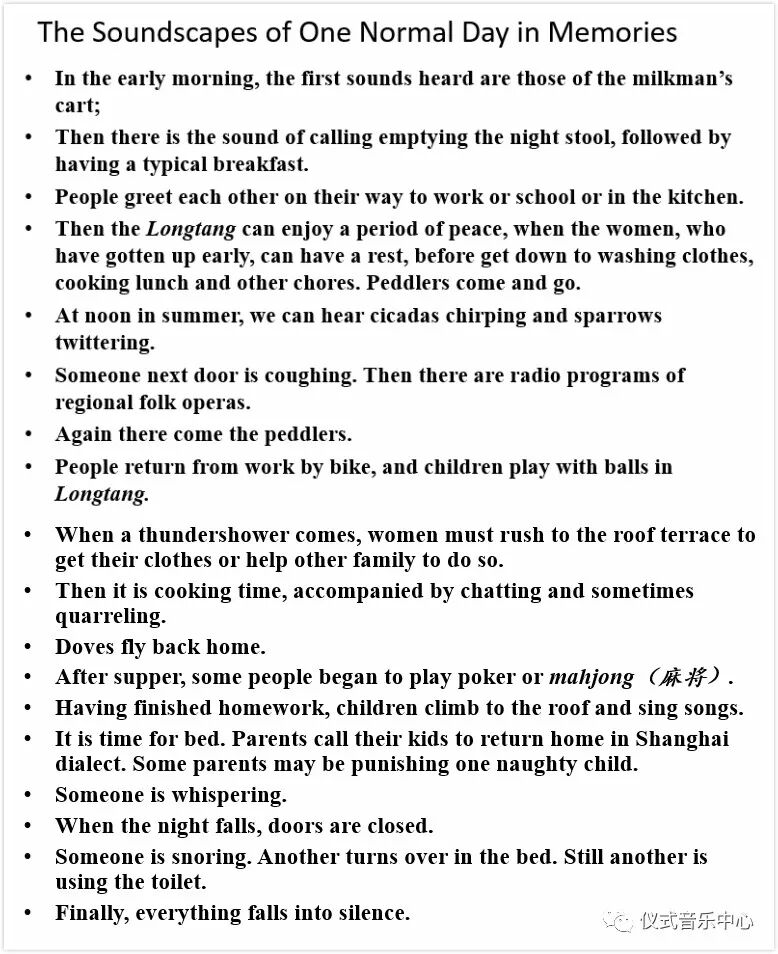

This young man is A Wen. He owns a cultural saloonanddedicated to the memory of old Shanghai. He depicted the soundscape of one normal day inlongtangas follows:

Shikuman and it’s sounds of Longtang, as “Backstreet cultural”ofShanghainese. I’d like to play a mixed recordingtoyou:

【弄堂一天】These sounds constitute an integral part of people’s memory of the old times in Shikumen. But now it is very difficult to record these sounds in one singlelongtang. The recording I played is collected from different longtangs and our collecting and edited together. So these are memoriesbeforethe 1990s.

Thusnostalgia is playing a prominent part in the current lives of the Shanghainese. Thatisvery personal experienceonmemories of the sound.

I will give you three little examples.

1. “When I was living in Shikumen, the place struck me as damp, dirty and chaotic; but now, whenever I return there, all I feelarewarmth and comfort.”

2. “Old dwellings, withitsparticular atmosphere, are something we can never get rid of.”

3. “I miss the chirping ofcricket. Now I still buy one or two, keeping them at home, only in order to listen to their chirping, which brings me back to the old times”.

“I would like to visit Tian Zi Fang. It ispropagatedas the best place to experience the culture of the old Shanghai’s longtang.”

“Seriously? Not possible. Can youhearShanghai dialect there? Does it have thelongtanglifeforreal?”

We deeply feel that the three elements of soundscape—keynote sound, sound signals and sound mark— proposed by Murray Schafer are altering with time and different human activities. The daily soundscape inlongtangin the past can be regardedaskeynote, which cannot be noticed by people who live there. Only when these people get out of this living space does the sound, lost or dying, become a unique mark.

The nicest memory of the sounds in Shikumen is that of peddlers’ yo-heave-ho and cicadas’ chirping.

At the end of my presentation, I would like to share with you one more phenomenon. We asked our interviewees about the daily sounds they hated the most. The most common answer is: the sound of upgrading the dwellings.( interior decoration)

(Nostalgia)When we posed a question to our interviewees: what is the biggest difference between the sound in Shikumen and that in the new districts? One answer is that they can hear more chirping of birds and insects, making them feel closer tothenature.

The change of residential styles will inevitably lead to the change of types of “family sounds” and cause a different sense of family identificationofthe old Shanghainese. If sound can shape the sense of place, people’s perception can be localized through sound (Feld, 1996). In the sense of place formed by the daily soundsinour investigation, experience of the present and memory of the past echo with one another.

The narrative of the traditional soundscape in Shikumen is based on a background that pieces together the present life and the past memory. And the lifeinthis city is and will be constantly changing into something new.

I would like to conclude my presentation with footage of an old famous film about the old Shanghai,Scenes of City Life.

Shanghai is a city built on tidal land, a city of migrants, a city which is quite young yet has a history of more than 150 years. What sound will we make in thisexpanse ofdark sea?

(Final audio file: sounds from construction sites, telephone ringing in the office, touching the keyboard of a computer, a folk song, loudspeaker of a peddler selling CDs )

From the memories of the old Shanghainese, we got to know that there are two kinds of cicada in Shanghai. One is big and dark brown; the other is small and green. Having recorded the cicada chirping in every district of Shanghai, we find that the sound of the small type has completely disappeared in downtown areas. And we eventually found suchchirpingin Pudong. Perhaps this suggests some changes in the evolution of insects for environmentalchanged.

总策划:萧梅

文字:萧梅

编辑:张毅

【声音研究专题】往期回顾

第1期 桑杰加措 |心弦:声音的曼荼罗

第5期 矫英 | 聆听: 声景(soundscape)研究之方法

第6期 罗晗绮 | 聆听“人与生态”:《生态音乐学》课程概述与思考

第7期 温和 | 野外录音中的听觉攀附及其文化省察——以蟋蟀的歌为例

第8期 高贺杰 | 声音的特写——纪录电影《触碰声音:格蕾妮的声音之旅》中的视觉音乐志描写

第11期 王苑媛 |现代性的声音景观——评米歇尔·希翁的《声音》

第12期 高贺杰 |“马”“鱼”“小孩”——生态视角下的鄂伦春歌唱

b站账号:仪式音乐中心

课程、讲座及工作坊视频持续更新中~

目录:

(1)萧梅《多元文化中的唱法分类体系》

(2)林晨《减字谱中的音乐形态》

(3)萧梅《“谁的呼麦”——亚欧草原寻踪》

(4)宁颖《从朝鲜族“盘索里”表演看“长短”的生成逻辑》

(5)崔晓娜《从音乐实践看“旋宫不转调”——以河北“十番乐”为例》